Court of North Carolina: A Hallowed, Beloved Green Space

Ahead of Veterans Day, look back on the Court of North Carolina's history as a haven for NC State's military community — and a landmark connecting generations of the Pack.

No place meant more to the Greatest Generation than the largest green space on NC State’s main campus, an open former pasture bounded by the school’s oldest academic buildings and shaded by massive willow oak trees that were planted as seedlings at the direction of inaugural President Alexander Quarles Holladay.

The open field – perfectly situated for between-class studying, lazy afternoon reflection and all forms of outdoor recreation – has been known by many names through the years: the Harris farm, the 1911 Field, Quonset Court, off-campus student parking and informally as the Court of the Carolinas.

Its right and true name, however, is the Court of North Carolina, as designated in the mid-1930s by the school’s Building the Grounds Committee.

This week, for Veterans Day, it will be decorated with hundreds of United States flags to honor NC State’s military history and the students, faculty, staff and alumni who have served in conflicts dating back to the Spanish American War.

The court — originally sold to the North Carolina College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts in 1896 by future president of the Board of Trustees and Wake County attorney J.C.L. Harris – is one of NC State’s nine original Hallowed Places, those designated buildings, landscapes and open spaces that have accrued special meaning over time to the campus community.

During 2023 Red and White Week, NASA astronaut and three-time NC State graduate Christina Koch said the Court of Carolinas was her favorite place on campus, using the name that crept into common usage between the 1970s and 1990s.

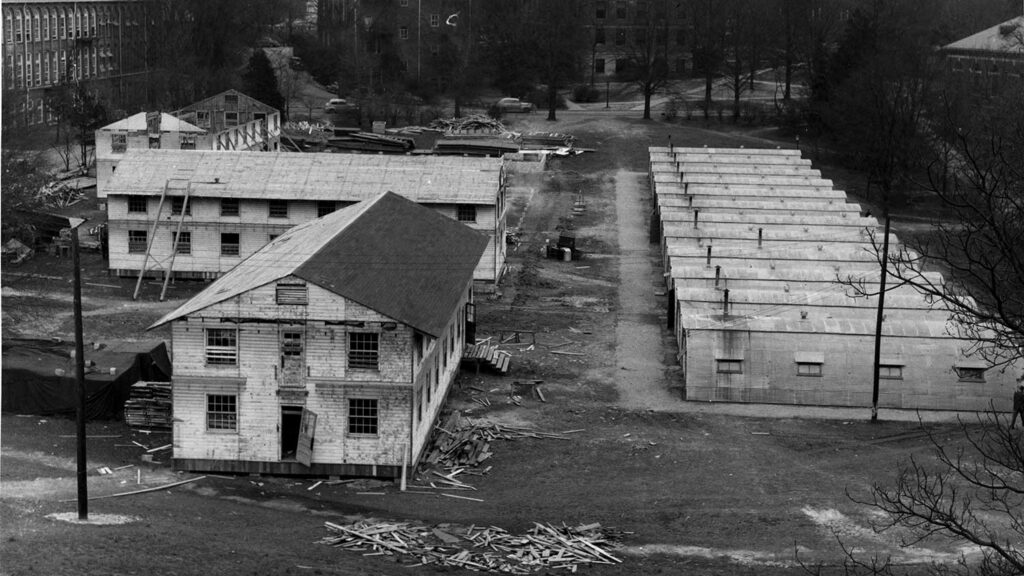

Generations of other students have also loved the court, particularly those who enrolled during and after World War II on the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, known popularly as the G.I. Bill. Why? Because it’s where they spent almost all their time in temporary classrooms made of military surplus Quonset huts and U.S. Army barracks that lined either side of the court.

They were unlit, unheated and a godsend for a campus that went from just under 700 enrolled students and 1,800 U.S. Army officer trainees in 1945 to more than 4,600 full-time students in 1946. There was simply not enough permanent space to accommodate such an increase in degree-seeking veterans and admitted students.

After the 1945 North Carolina legislature failed to provide construction funds for the expanding college, the school purchased 22 temporary buildings to create 52 classrooms for students and 20 offices for professors, putting them in the courtyard and several other places around the compact original campus. To go with the temporary classrooms, the school built trailers, mobile homes and other prefabricated buildings on the western edge of campus called Trailwood and Vetville to house all the new students, most of whom were married and some of whom had children.

A total of 12 Quonset huts and four barracks buildings were located in the heart of the court for the flood of new students.

“Ugly, but necessary…” declared Technician.

The surplus buildings were intended as a temporary solution for the classroom shortage but were used until 1953, when they were relocated to other parts of campus and the court was turned into “a newly opened haven for off-campus parking” for up to 3,200 cars, according to a 1953 Technician story.

Parking areas, always a contentious issue on campus, were debated for the next 20 years, including a three-phase plan introduced in 1967 that would have razed both Tompkins and Winston halls to build a parking deck that stretched from Hillsborough Street through the heart of the court.

Fortunately, the area was never paved, and the unmarked gravel parking spaces, accessed by a now-closed portion of Primrose Avenue between it and Winston and Tompkins halls, lasted less than a decade.

The green space returned in the 1960s, though original architectural plans had a unique prefab stone slab educational building located directly in the center of the courtyard with green alleys on either side. That idea died in planning and Poe Hall was pushed to the outer edge, between Leazar and Page halls.

The court became a campus gathering spot, surrounded by native trees and shrubs and flower beds. (A long-standing myth that the court was ringed by 100 trees to represent North Carolina’s 100 counties is disproved by the logic of available space.)

Day-long outdoor concerts sponsored by the Union Activities Board were attempted in the 1970s, including both The Day and Zoo Day festivals, but Hillsborough Street merchants did not like the traffic and noise created by partying college students – unlike those of today who manage just fine during Packapalooza.

After a rowdy concert in 1976, outdoor festivals were returned to the John Miller Intramural Fields behind Carmichael Gymnasium.

Primrose Avenue and other streets near the court were blocked in 1979 to make room for the Link Building, a humanities-focused addition that joined Tompkins and Winston halls. It is now called Caldwell Hall, in memory of Chancellor John T. Caldwell.

As the university prepared for its yearlong centennial celebration during the 1986-87 school year, Chancellor Bruce R. Poulton officially ended any chance that the court would be used for anything other than a pleasant, nicely landscaped place to gather.

At the time, NC State was beginning to develop its second land grant from the state of North Carolina, a 1,100-acre tract on the historical Dorothea Dix Hospital property south of Western Boulevard that more than doubled the size of the university’s developed property.

It was called Centennial Campus.

On Sept. 3, 1986, Poulton and student government leaders unveiled The Centennial Boulder, a 2-ton gneiss rock that was transported from the new campus to a spot under one of the willow oaks behind Peele Hall, where it remains today. Then-student body president Gary Mauney called it “a bridgeway of the achievement that was and the excellence to come” and a “symbol of unity between the two campuses.”

A bronze plaque on the stone, not unlike the standing signs that designate current Hallowed Places on campus, reads: “This pleasant open space is surrounded by some of the oldest buildings on campus. It has been well-loved by faculty and students alike for a century and is today dedicated to them and to future generations.”

At the end of the 20-minute unveiling, Poulton said, “No one will ever build a building on one square inch of this courtyard.”

No one will ever build a building on one square inch of this courtyard.

“What I keep thinking about is what a supercool and robust campus we had,” said Mauney, now a lawyer in Charlotte. “From that very green courtyard, to the very red Brickyard to the rainbow colors of the Free Expression Tunnel.

“All of them were beautiful and symbolic to me.”

There have been several significant proposals to change the look of the court, according to former university architect Edwin “Abie” Harris, who developed various plans surrounding the green space.

In the early 1970s, thanks to educational bonds given by the state of North Carolina Legislature, a new interdisciplinary educational building was designed for the site of the westernmost boundary of the court, on the site of the 1911 Building. Constructed in 1908 and named in honor of the 1911 graduating class, the Victorian-style building with the Doric veranda was the largest dormitory at a southern college, but it has changed occupants through the years.

A new $12 million multipurpose facility for the College of Humanities and Social Sciences, with a large glass galleria, a bookstore and food service, was designed to serve as a pathway between Gardner Arboretum on Agriculture Hill and the Court of North Carolina. Most of the funding from the bond, however, went into the construction of the University Student Center (now Talley Student Union) south of the railroad tracks.

In 2005, Professor of Design Robert Burns drew plans to recreate Raleigh’s famed Catalano House with a covered pavilion that had the same hyperbolic paraboloid roof as the original home between Tompkins and Poe halls, cutting into about one-third of the existing courtyard.

There have been improvements through the years. The senior class of 1987 raised more than $125,000 to construct an outdoor classroom just outside of Tompkins Hall. In 2002, as part of new landscaping for the 1911 Building, new brickwork, staircases and walkways made the Court more accessible for all who travel campus.

Other landscaping features were added in 2008, including a second outdoor classroom at the southwest corner of the court.

But, in keeping Poulton’s promise, no permanent buildings have been added to the court for more than four decades, and it remains a place that connects generations within the NC State community.

- Categories: