Let It Bee

Horticultural science professor Danesha Seth Carley helped reintroduce native plants to the Pinehurst No. 2 golf course for its 2014 men’s and women’s U.S. Open championships. Since then, she’s focused on bringing bees back to Donald Ross’s original design for the course.

Ten years ago, when the United States Golf Association and Pinehurst Resort pulled off the first-ever back-to-back U.S. Open Championships for men’s and women’s golf, NC State horticultural science professor Danesha Seth Carley lent her expertise to identify dozens of native plants that helped the renovated Pinehurst No. 2 golf course pull off the unique feat.

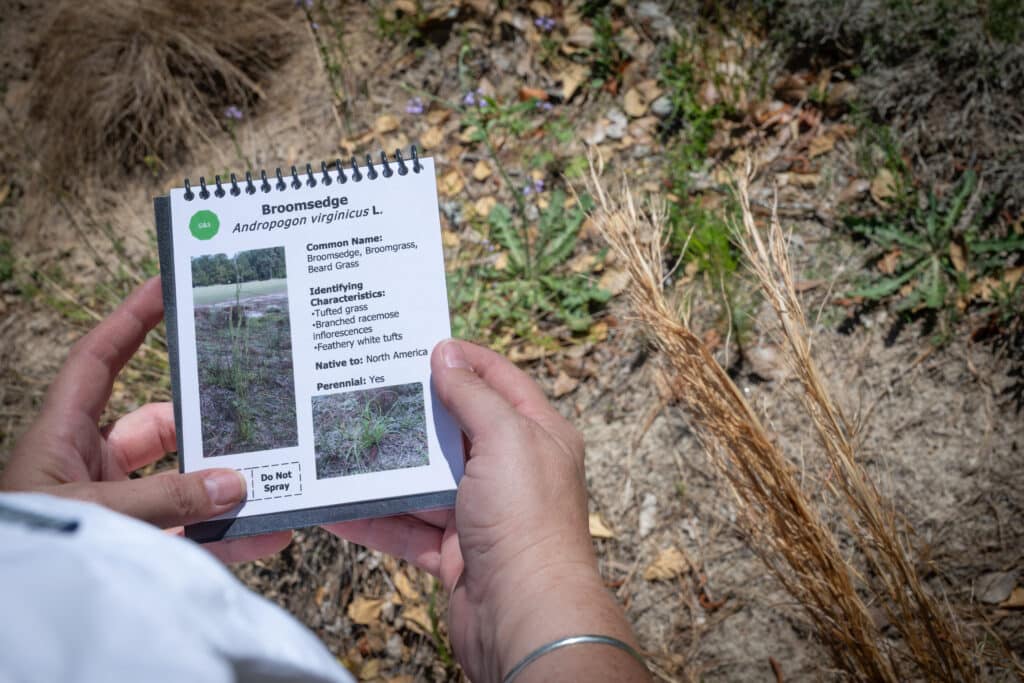

She and her four NC State graduate students published unique pocket-sized guidebooks that Pinehurst staff used to identify which plants to eliminate and which to keep as they returned the course to a rougher, more natural look. Under the guidance of designers Bill Coore and Ben Crenshaw, Pinehurst removed some 900 sprinkler heads, converted hundreds of acres of water-guzzling bermudagrass to natural vegetation, and reduced a single course’s water usage from 50 million gallons a year to less than 9 million gallons as part of their 2010-11 renovation.

That renovation and installation of native plants was the dominant story of the 2014 double Opens hosted at No. 2, a remarkable turnaround for a course that had tried for four decades to get back to famed designer Donald Ross’s original intent for his most iconic design.

Since Pinehurst hosted the men’s and women’s Opens in successive weeks 10 years ago, Carley has changed the focus of her research. She still works regularly with the resort, one of the largest golf centers in the world, to foster growth of the plants that naturally occur in the pine barrens of the Sandhills; but today she’s also studying the insects that are attracted to them.

Now, she’s all about the bees.

“I’ve become very pollinator-centric at this point in my career,” Carley says.

That’s still a benefit to North Carolina’s ever-growing golf industry, which includes 550 golf courses and some 55,000 jobs, adding some $3 billion to the state’s economy annually.

Restoring Bee Populations

When the Open holds the four-day championship competition June 13-16 at the Moore County location, the course will be buzzing with bees and other pollinators that are native to the ancient Sandhills in a way that was absent from the three previous Opens.

While there were no official population counts prior to the events in 1999, 2005 and 2014, Carley and her students have noticed an anecdotal increase in multiple varieties of bees in the Pinehurst area, attributable to the return of native North Carolina plants that were crucial to the significant course renovation by the nationally known design firm.

Carley, the director of NC State’s Center for Integrated Pest Management, has spent hundreds of hours at Pinehurst No. 2, working with several NC State alumni who serve as course and green superintendents at the resort and USGA researchers to make sure the 7,500-yard, par-70 golf course has a healthy bee population that matches the Sandhill-native plants that she helped identify more than a dozen years ago.

“Bees are the unsung heroes of our urban landscapes, tirelessly working to pollinate native plants and ensure the vibrant biodiversity that makes cities and rural areas thrive,” Carley says. “Protecting bee populations is not just an environmental necessity, but a commitment to preserving the natural beauty and ecological balance, especially within urban spaces.”

As part of her efforts to strengthen bee populations, Carley published a book with Anne M. Spafford, Pollinator Gardening for the South (UNC Press, 2021), about bringing pollinators into backyard gardens and shared community spaces. She has also updated the native plant guidebook she originally made for Pinehurst’s maintenance staff to include special designations for pollinators that help current staff protect them as they mow, rake and remove unwanted plants from the course.

Not every native plant is pollinator friendly, of course, but those that aren’t often serve as hosts for bees as they lay their eggs and search for food.

Some of those plants include wild bergamot (also known as “bee balm”), pine weed, false dandelion and yellow toadflax. Other plants, such as broom sedge and the native wiregrass that has long been identified with No. 2’s natural areas, provide nesting areas for pollinators. There are even some areas on the course that include one of Carley’s favorite native plants, the tall bushy bluestems with cotton-candy flowerheads that can often be seen on Sandhill roadsides.

Using the preferred bee population management research, some of which comes from NC State Extension apiculturist and associate professor of ecology David Tarpy’s lab and the work of his postdoc Hannah Levinson, Carley and her students hope to continue facilitating the return of bees to the native habitat they have helped create, whether they are exotic honey bees or native sweat bees and bumble bees.

“I think the diversity of the bee population is something that is beautiful to see in a place that is designed to be beautiful for golfers, for spectators and for anyone who visits the resort for whatever reason,” Carley says.

A Nonresort Background

Carley is hardly a typical golf resort patron or country club member, though she did take some time after 2014 to learn to play — and eventually abandon — the frustratingly fun ancient Scottish game.

She grew up in an Appalachian commune with hippie parents in the hills of West Virginia, with few modern conveniences: no electricity, no running water, few indoor amenities. After spending so much of her time outdoors in her youth, she quickly decided to pursue an academic career in ecology.

She earned a degree in biology at Earlham College in Indiana in 1998, a master’s degree in entomology and plant pathology from the University of Tennessee in 2001 and a Ph.D. in crop science and plant pathology from NC State in 2006.

Carley’s parents were mortified when they learned that NC State sustainability professor Tom Rufty had asked her to work at Pinehurst, which at the time had more lush bermudagrass fairways and rough than waste areas filled with native plants and wiregrass.

“My parents thought I was turning my back on the environmental movement they were part of when I was growing up,” she says. “But they’d always taught me that you can effect greater change from within a system than from without.

“So I told them, ‘I’m in the system now, and I’m working for the greater good. They are going to be here and do things anyway, so I’m going to help them do it better.’”

Since it was built at the turn of the 20th century, the Pinehurst Resort has had a varied history of development, from the sand fairways and greens Ross originally designed and worked on throughout his life to the corporate ownership of the 1970s to the redevelopment for championship venues since the 1990s.

“This is a huge public resource for the state of North Carolina,” Carley says. “It was originally founded as a health resort, meant to help get people out, to help with their mental and physical health. We can give the community what it wants but also make sure it is environmentally thoughtful and fostering of biodiversity.

“We’ve reduced the amount of water, pesticides and labor used here and made it a more environmentally sustainable place.”

Pinehurst No. 2 course superintendent John Jeffrey ‘00 (B.S. agronomy, with a turfgrass concentration) says those were not the reasons for bringing native plants and pollinators back to the golf course, which originally was built under Ross’s watchful eye in 1907. They were, however, happy benefits of returning the course to Ross’s original design, as seen in a high-definition photo taken by a Fort Bragg aviator on Christmas Day in 1943.

We can give the community what it wants but also make sure it is environmentally thoughtful and fostering of biodiversity.

“It showed the course the way it was before it had irrigation lines planted underground and before there was bermudagrass planted off the fairways,” he says. “It’s the way Ross intended for it to look.”

Carley is proud of her role in that outcome. She maintains a regular relationship with the superintendents and maintenance staff at the course, where she’s welcome to arrive in her car with the “Bee Hugger” bumper sticker, grab a golf cart and show off the native plants and pollinators she and her graduate students have catalogued during their 15 years of research at the course.

In the end, this year’s Open will be one of the most sustainable ever conducted by the USGA, which says this championship will be the 1,000th ever conducted by American golf’s governing body. It’s a benefit of the USGA’s designation of Pinehurst No. 2 in 2020 as its first anchor site, with the Open returning this year and in 2029, ’35 and ’47.

In the aftermath of replacing the course’s bentgrass greens with ultradwarf bermudagrass following the 2014 Opens, the resort also buried utility lines that replaced the need for portable generators during the competition, saving some 50,000 gallons of diesel fuel, and added permanent water lines to aid concession and corporate hospitality suites.

So the 40,000 spectators per day who will be on the grounds for practice and competition rounds will leave a smaller footprint on the environment. That, coupled with Carley’s research, is a huge benefit to North Carolina’s golf industry, just as NC State’s Lonnie Poole Golf Course has been since it opened on Centennial Campus in 2009.

And that’s something both Carley and her parents can appreciate.

- Categories: