Poetry Collection Reflects On Raleigh, City Life

Jon Thompson’s fourth book of poetry, Notebook of Last Things, reflects at length on an unnamed city; its growth, its constant reinvention, and how its citizens interact with it. While the city is not named in any of the poems, it is Raleigh.

This is not surprising, given that Thompson – a professor of English at NC State – has long called Raleigh home.

How often does one get the chance to interview a poet who has written an entire book of poems about your city? We knew we had to take advantage of this opportunity.

The Abstract: Before I ask about your new book of poems, Notebook of Last Things, I’d like to ask about two of your previous books of poetry, Landscape With Light (Shearsman Books, 2014) and Strange Country (Shearsman Books, 2016). Both of those were about place, but in different ways. Landscape seemed more a visual exploration of place, while Strange Country seemed more about the social and cultural peculiarities that make the United States what it is. How would you describe Landscape and Strange Country?

Jon Thompson: Landscape with Light was a collection that meditated on American landscapes (and cityscapes) but the point-of-departure was the imagery of landscapes in iconic American films. I was fascinated by the striking presence, or sometimes the striking absence, of American landscapes in our collective consciousness – think of North by Northwest or Badlands or Deliverance or even the Wizard of Oz. To me, these landscapes embody some of our most defining myths – landscapes as a source of beauty; landscapes as a source of a new self; as a source of social regeneration; landscapes as wealth, and so on. Landscape with Light was interested in grappling with the power and richness of those landscapes in the American imagination, including of course, my own.

Strange Country has many affinities with Landscape with Light but it is not focused on landscapes per se. It is, however, very much a reckoning with as you put it, “the social peculiarities that make the United States what it is”: another way of putting this is that the book is interested in exploring the strangeness of our norms and culture, not least in regard to the beliefs that animate us. I was intent upon capturing a sense of place: for me, place seems to say so much about our identity and values. Hard to reckon with “Americanness” without factoring that in. Our identity comes out of the ground, so to speak – or more accurately, what we have done to it, or long to do to it.

TA: Notebook of Last Things also seems to be very much a book about place. Are the poems about a specific place, or were you writing about a place that exists only in your imagination?

Thompson: All of the poems address themselves to an unnamed, mid-Atlantic city undergoing a process of rapid growth and transformation. The city is never named, but it is Raleigh, or my response to Raleigh. I didn’t explicitly identify the city as Raleigh in the collection because I wanted readers to come to the book without preconceptions, and I wanted the book to address the kind of urban experience that many mid-Atlantic cities are now undergoing without isolating that experience exclusively to the city I am living in. So to answer your question directly, the poems are very much about a specific place but ultimately that place as it gets filtered through my imagination.

TA: How would you characterize the themes that you explore in Notebook? What sets this collection apart from your earlier explorations of place and time?

Thompson: In Notebook of Last Things I wanted to address what the “here-and-now” is like – what it looks like, what if feels like and how it reverberates in the mind. The title of the collection refers to the ephemerality of experience – the way that any phenomenon that exists at any moment can be thought of as the first and last expression of that thing. The collection is written as three numbered sequences. Each sequence is made up of tercets or three-line stanzas. On each page there are three numbered poems. So the poems are very short, but hopefully, they work to create a mosaic of the city at a particular time. While short, the poems are not haiku poems or tanka poems, but they are influenced by the brevity of those forms and their sensibility. One of the epigraphs to the book is a poem by the famous Japanese poet Bashō:

Come, see real

flowers

of this painful world.

I love the fragility and ferocity of this poem. Bashō’s poem gets at the paradoxical quality of experience – the way, for instance, beauty and pain are bound up with one another in human experience. Due to their concentration of people, systems, cultures and institutions, cities are full of these paradoxes or apparent contradictions: I wanted to explore in this collection what it feels like to live with/through all that. But I also wanted other frames of reference. In particular, I wanted to include a sense of how history, that absent presence, makes up the contemporary world. I drew on a figure from Renaissance paintings, the Recording Angel, and included it in the collection as someone or something I could address, and as a perspective that goes well beyond the here-and-now.

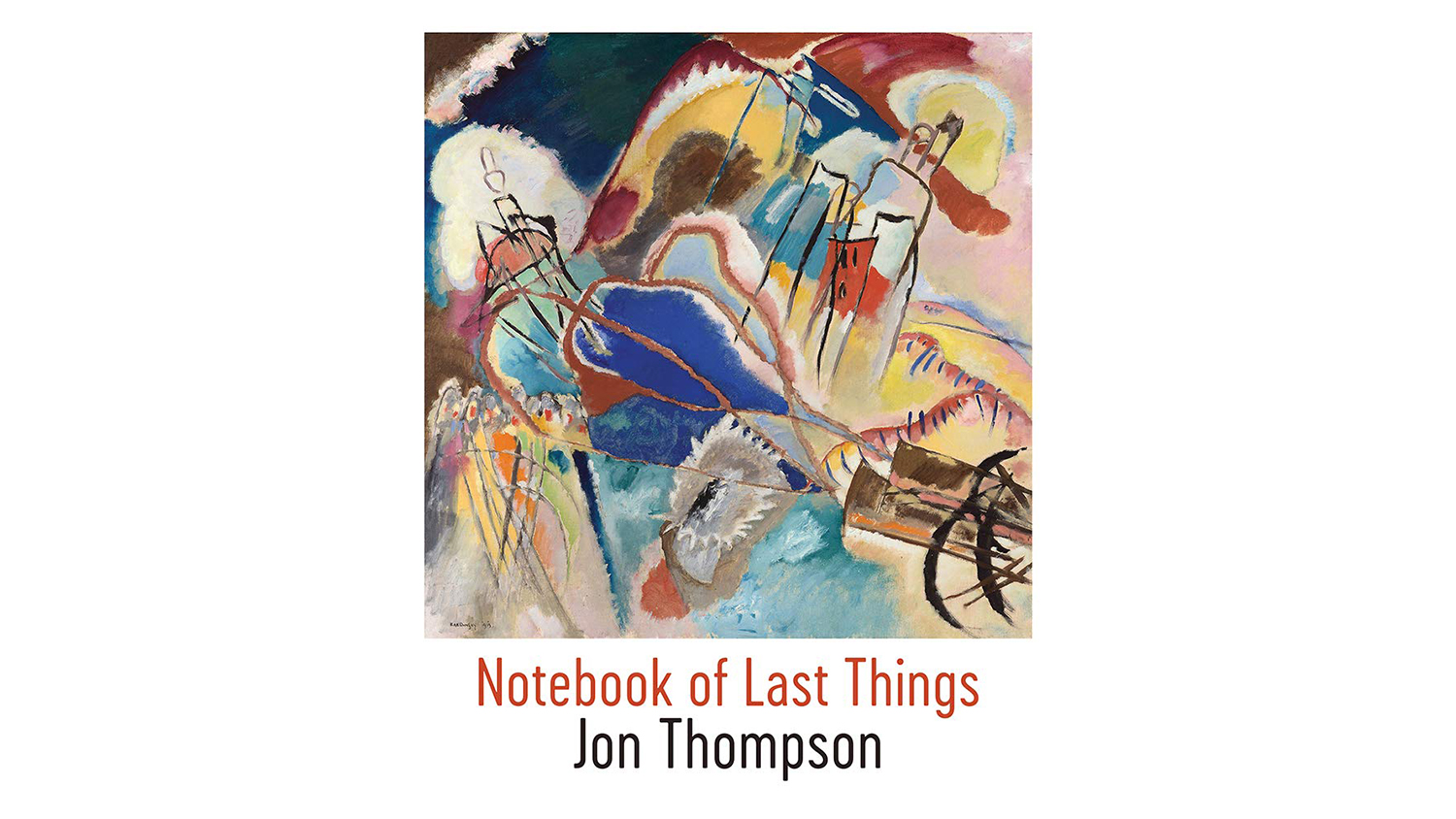

Another frame of reference in the book is captured in the cover image. I was very pleased to be able to use a reproduction of Vasily Kandinsky’s 1913 painting, “Improvisation No. 30 (Cannons),” which is a sort of dream-like jumble of abstracted images all in different colors – with the exception of a cannon in the lower right-hand side of the painting. (Note: this is the image on the cover of Thompson’s book — and at the top of this page.) While I wanted Notebook of Last Things to focus compositionally on the experience of living in a particular urban space, I wanted it also to capture the reverb of the world outside it. As I was writing the collection, the Syrian city of Aleppo was being systematically dismantled, so as a counterpoint, the collection refers also to that human catastrophe: “So that city the world chooses to forget, city of those who’d/rather be ghosts than living, city’s that’s been destroyed, is/destroyed again. And the Temple that was buried is buried again.”

TA: This is the fourth collection of poetry that you’ve published. How has the experience of publishing poetry changed for you over time? Has the process of writing a collection changed for you over time, given that you’ve now done it several times?

Thompson: It’s a process of continual discovery. On the one hand, there’s a heightened awareness of form, and I hope, greater formal control and range, but alongside that, for me, there’s the imperative to make language emotionally, dramatically compelling. Poetry is most compelling to me as “thought-as-feeling” and “feeling-as-thought” but if it becomes too ratiocinative it loses its dramatic urgency. I’m mindful of the importance of maintaining that balance. Making art, making poetry, by definition is an activity that requires that one commit oneself to discovery, to leaving the shore behind as Faulkner put it. Living with uncertainty, making it central to writing, doesn’t get any easier – at least for me – but it remains key.

TA: Poetry is a little different from many other forms of writing, in that very few people have ever tried writing a novel or a play – but many people have tried writing poetry. How, if at all, do you think this affects the nature of the relationship between the poet and the reader? Are they more appreciative? More critical?

Thompson: Hard to say. The ecosystem of poetry in the U.S. is very odd – contemporary American poetry is flourishing, but only on the margins of American life. In this country, it’s a major art form with a minor audience. Many people have written verse in school or out of it, often in response to a personal crisis. This can lead to a sense that any projection of words on the page is poetry, or that all poetry should be as accessible as the lovelorn expression of a heart-broken adolescent. Oscar Wilde once noted that, “All bad art springs from genuine feeling.” I think that is right. On the other hand, some adolescents who have written gauche verse when young have turned themselves into interesting poets over time. I think the key thing is to make the effort to engage poetry on its own terms rather than expect poetry to conform to a single paradigm of what poetry is, especially if that paradigm is unaware of the real diversity of poetic traditions in the world.

TA: Any advice for aspiring poets out there?

Thompson: Read broadly. Read deeply. Think of learning to write poetry as a craft that takes a lifetime to master. Write, write, write. Then learn the craft of revision. Be willing to go into the valley of darkness. Repeat.

- Categories: