Lessons From a Pandemic

No one survives a pandemic untouched by the experience, says NC State editorial director David Hunt. In a first-person account of his work covering the AIDS crisis in the 1980s, Hunt sees parallels with today's coronavirus outbreak.

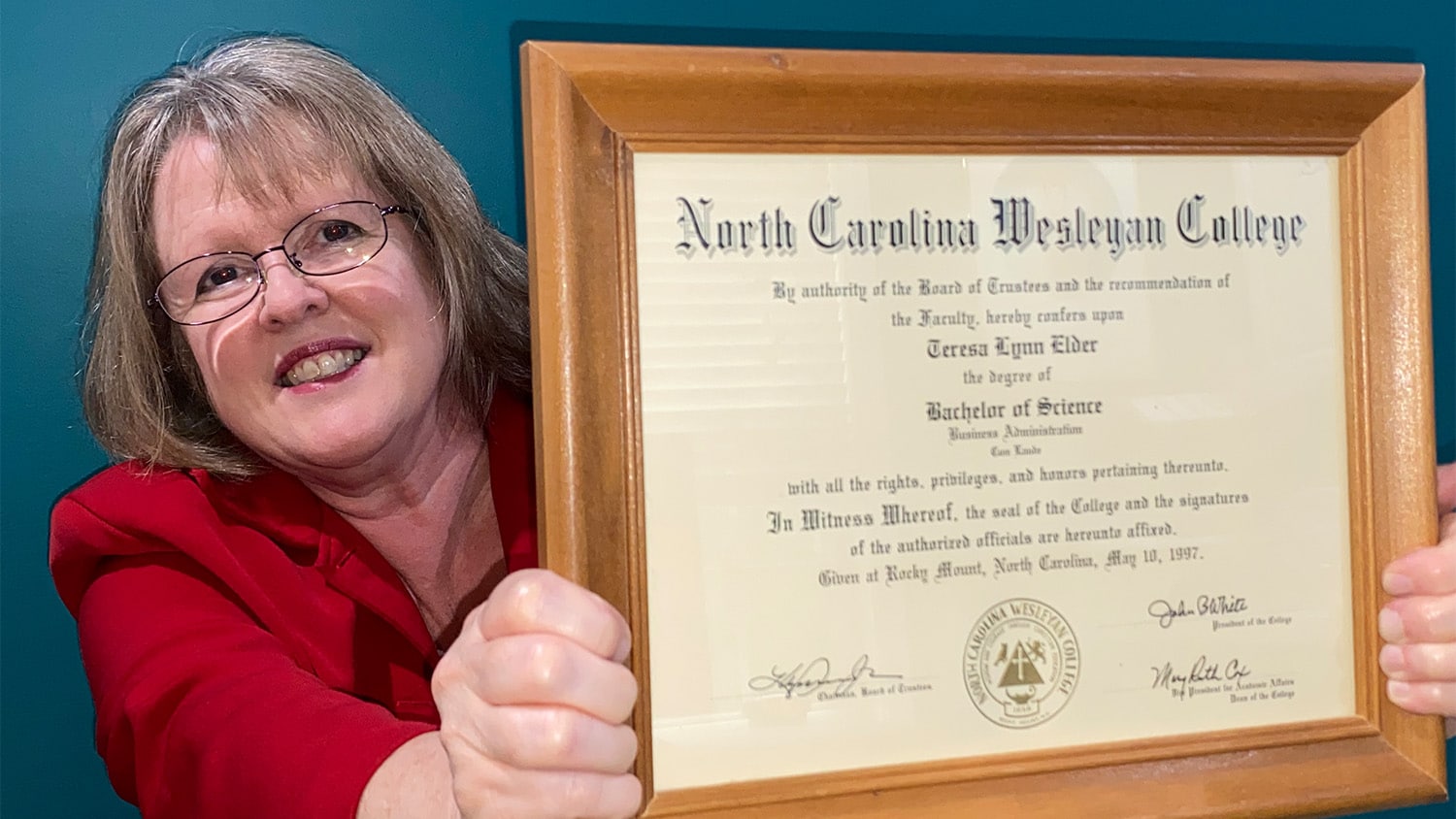

Voices is a new series of first-person narratives written by members of the NC State community reflecting on experiences that have shaped their personal and professional lives. David Hunt is director of editorial services in University Communications and Marketing.

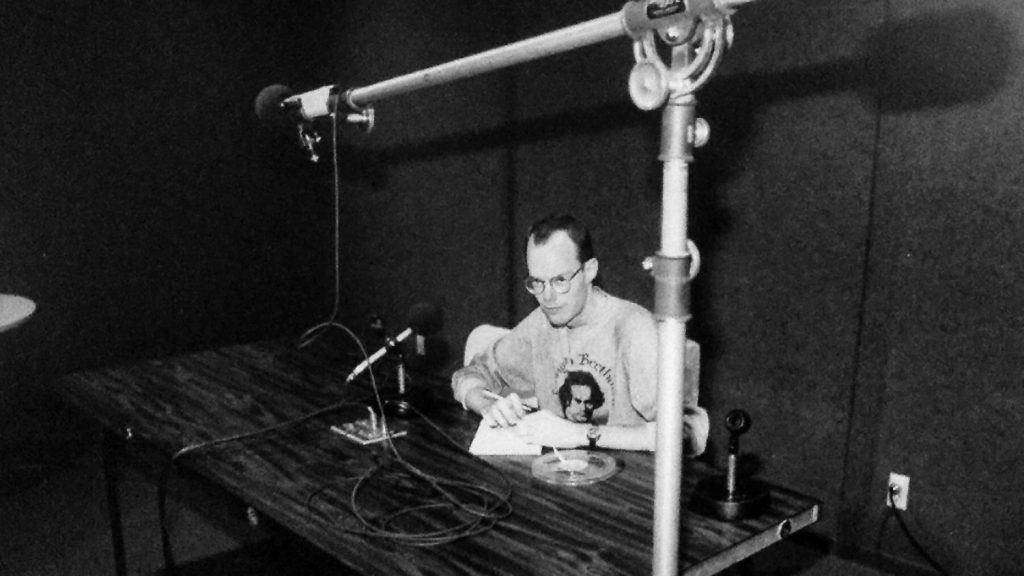

In 1981, I was working at public radio station KPFK in Los Angeles when I reported on a mysterious disease outbreak: 41 cases of a rare form of skin cancer and opportunistic infections had been diagnosed in gay men in L.A., New York and San Francisco. Over the next four years, I covered the progression of this new disease — the acquired immune deficiency syndrome — as it grew into a major public health crisis.

By the time I left KPFK in 1985, an estimated 100,000 Americans had been exposed to the human immunodeficiency virus, the pathogen responsible for AIDS. More than 13,000 of them had died.

Worldwide, AIDS-related illnesses have claimed more than 32 million lives since 1981, making AIDS one of history’s deadliest pandemics.

Learning on the Job

I don’t suppose anyone living and working in the middle of a pandemic comes away from the experience untouched. When I listen to some of my old news reports and documentaries from those years, I can’t help wondering if I did enough to alert people to the threat of the emerging disease. I advised listeners to stay informed, but there were few resources available to help the people most at risk. Safer-sex guidelines that we take for granted today simply didn’t exist in the first two years of the outbreak.

Here are a few things I learned on the job as a reporter covering the AIDS crisis that are relevant to today’s novel coronavirus pandemic.

Statistics Don’t Tell the Whole Story

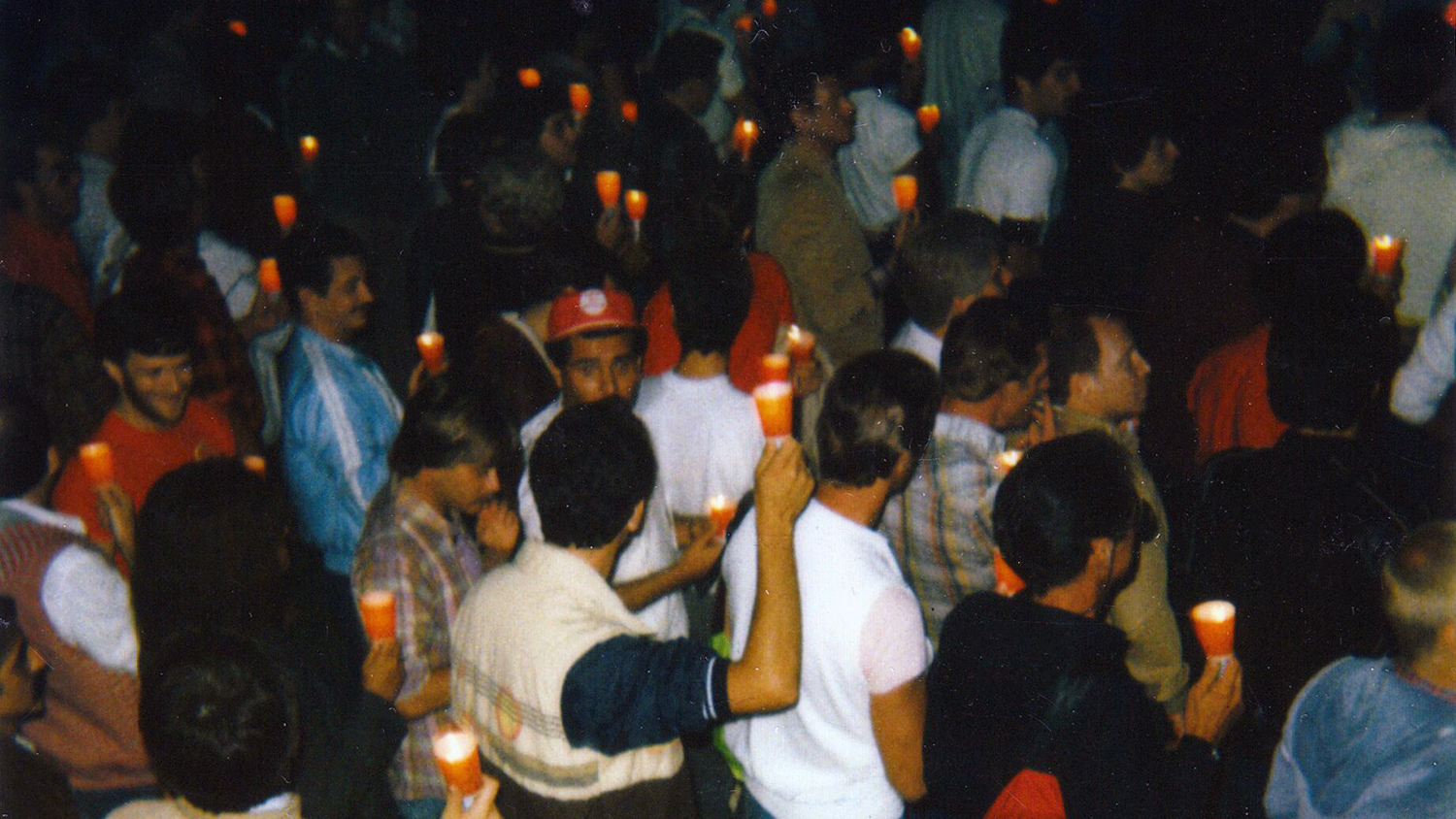

In 1982 I attended a public meeting in L.A.’s gay community featuring several local physicians. Many in the audience were concerned about the growing number of cases of so-called “gay cancer” and “gay pneumonia.”

One of the doctors urged attendees to put the disease outbreak into perspective, noting that only a few thousand people had been diagnosed with these ailments. In a country of more than 200 million people, the outbreak was “statistically insignificant,” he said.

By focusing on the relatively small number of cases, the doctor missed the larger issue: many in the audience were at risk for the disease, which has a long incubation period. If the audience members had known the disease was caused by a virus that was silently spreading in their community, the people most at risk for HIV could have taken steps to reduce their risk.

You can find similar thinking on social media today, with people downplaying the risk of COVID-19 and comparing it to the seasonal flu. Since no one has natural immunity to the novel coronavirus, the risk of exposure is real and significant.

Stigma Slows the Response

Like plague victims in the Middle Ages, people who had AIDS in the early days of the pandemic faced social ostracism and discrimination. Some people with AIDS — as well as those simply suspected of having it — were evicted from their homes, fired from their jobs and shunned by family and friends. The AIDS backlash, as it was called in the media, even prompted an increase in physical violence against gay men.

With the discovery that HIV causes AIDS in 1983, public health officials could finally begin to target the disease through research to find a vaccine or cure. They also undertook education efforts to warn the public about risky behaviors — but at first the stigma attached to AIDS slowed these efforts.

In 1985, when the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention proposed an initial prevention plan with a price tag of $37 million (about .004% of that year’s federal budget), the White House rejected it. Not until 1987, when the virus began spreading beyond the initial high-risk groups, did the federal government mount a nationwide public education campaign.

Today, people from so-called coronavirus hot spots such as New York and New Jersey find themselves unwelcome in other states. But as we learned from the AIDS pandemic, the best response is to target the disease, not people at risk for it.

Put a Face on the Disease

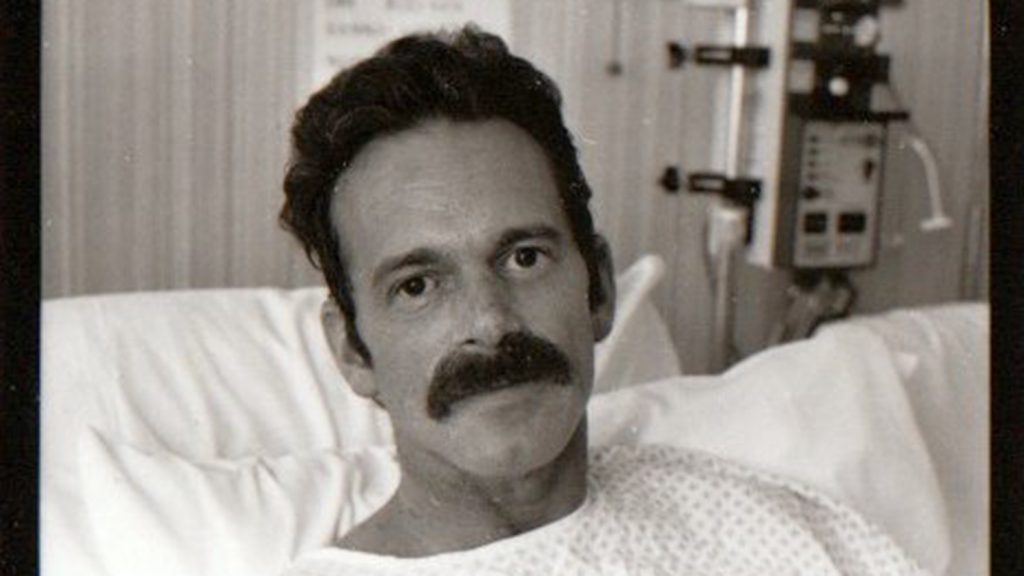

In 1983 I produced a half-hour radio documentary featuring two men who had been diagnosed with AIDS. It was the first time people with AIDS had been given the opportunity to tell their stories on a broadcast outlet in Southern California.

One of the men, Bobbi Campbell, was the 16th person diagnosed with AIDS in San Francisco. He called for more public awareness of the disease, but he also urged people not to panic and not to blame the people suffering from the disease for their own plight. Campbell became an AIDS activist, later appearing on the cover of Newsweek and on the CBS Evening News. He wore a button bearing the words “I Will Survive,” using the title of the popular disco anthem to inspire hope in the outbreak’s darkest days.

Putting a face on the disease helped to humanize the crisis and to highlight the courage and resiliency of people on the front lines of the pandemic. It also helped listeners understand that the disease could affect people like them.

The same is true today as we confront COVID-19. While it’s important to pay attention to messages from government leaders and public health officials, don’t forget to listen to and share the stories of people suffering from or treating the disease. Their stories can provide important insights into the impact of the crisis and influence others to reduce risky behaviors.

It Will Scare You

In 1982 I read a medical journal article that correctly suggested that AIDS was most likely caused by a virus that could be transmitted during sex. It only took me a few seconds to connect the dots: A fatal disease with no cure may have been spreading in L.A.’s gay community for years. As a gay man, I feared the worst. This will probably kill me, I thought. This will probably kill all my friends.

Reporting on a disease that you’re at risk of contracting is incredibly difficult. It’s tough to maintain any kind of professional detachment and objectivity, to report facts and not fears. If you start the day checking yourself for purple lesions, you’re closer to the story than you should be, I told myself. But with the number of AIDS cases doubling every six months and few news outlets covering the story, I felt I had no choice.

Today, we’re all at risk for contracting a new and virulent disease. You don’t have to be a reporter interviewing patients and health care professionals; just shopping for your family can increase your risk.

If we acknowledge that reality, it doesn’t diminish the fear, but it can help us function as best we can in spite of the fear. And it can help us see each day as a gift.

It Will Change You

I stopped reporting on the AIDS pandemic in late 1985. The story was finally getting some national news coverage, and the CDC had announced the development of an HIV test. I believed that a vaccine would be developed within a year.

I decided to focus my attention on helping to promote public health. A friend and I started a video production company producing health education videos, including a video for the parents and caregivers of children with HIV/AIDS.

A decade later I took a job at a public health agency, where I had the opportunity to develop outreach programs to combat some of society’s most intractable problems, such as domestic violence, eating disorders and depression. I also published a health magazine to promote wellness and the treatment and prevention of disease.

In the decades since the AIDS crisis, my life has taken me from journalism to health education to higher education — a journey I could not have envisioned when I began my career at a weekly newspaper in 1975.

Today, I remember the many courageous AIDS activists and medical professionals I interviewed during the pandemic — people who continue to inspire me to do my best in difficult times. Although Bobbi Campbell did not survive the AIDS pandemic, his message of hope did. As the nation confronts another pandemic, I hold fast to that promise: We will survive.

- Categories: