Settling the Score (Board)

From a slab of wood to the 11th-largest display board in college football, the Wolfpack has always found innovative ways to keep score and entertain fans.

Imagine a time when fans attending a college football game had no real idea of the score or how much time remained in a contest.

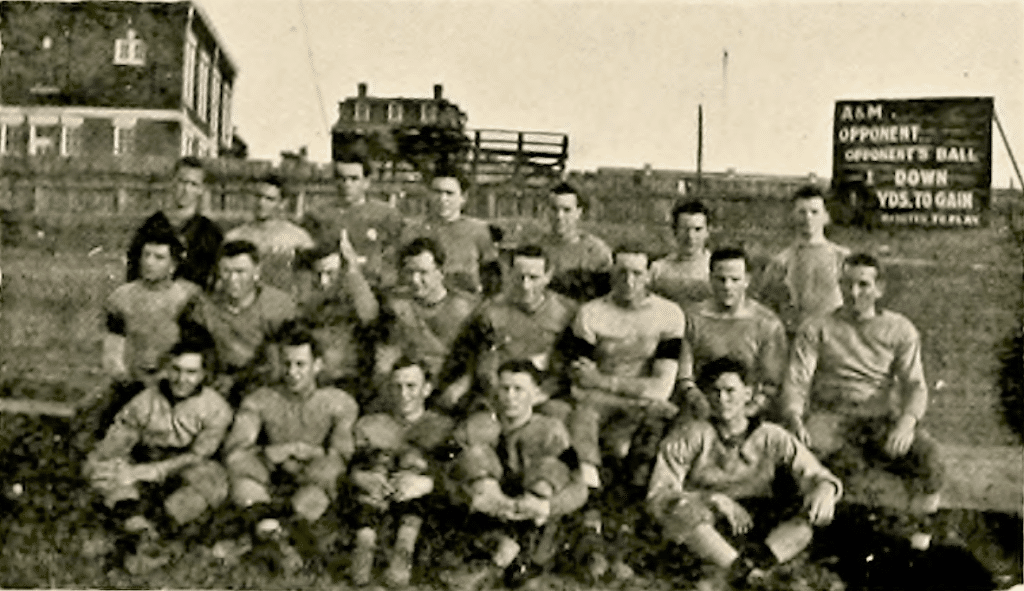

For years, that was the case at old Riddick Field/Stadium, NC State College’s former on-campus home for football — back before helmets, facemasks or shoulder pads. Riddick’s first real scoreboard, homemade at the school’s student-run wood shop, made its debut on Oct. 7, 1911, five years after the New Athletic Field (as Riddick was initially called) hosted its first varsity game.

That scoreboard was rudimentary compared to the giant $15 million videoboard and sound system that will be unveiled Saturday at Carter-Finley Stadium in the Wolfpack’s 2023 home opener against Notre Dame. Kickoff is at noon.

Manufactured and installed by Daktronics, the scoreboard is 7,121 square feet, boasting 6.6 million pixels and 75 audio speakers. It is believed to be the 11th largest single-display board at a college football stadium.

At 166 feet wide, the new board is 50 feet wider than the Memorial Tower is tall. It is one of many off-season enhancements added to the Wolfpack’s home of football since 1966.

In contrast, the 1911 scoreboard, modeled after a similar board at Cornell University, was 11 feet wide by 9 feet tall and offered little in the way of information. It had just the score, the down and yards to go for a first down. Time was kept by a lineman on the field, so fans were unaware of how much time remained until a whistle blew at the end of each quarter.

Still, it made a big difference for the thousands of still-learning fans who attended the game.

“An improvement in evidence yesterday was a bulletin board under the charge of some second-string men who knew football well enough to record the progress of the game for the benefit of the crowd,” wrote Raleigh’s The News and Observer. “The bulletin board showed immediately after each play the side having possession of the ball, the down (whether first, second or third) and the number of yards to gain, together with the total score. Football is so difficult to follow, if not enjoy, that this innovation is decidedly popular.

“Be it confessed also that some of the mere men who will be present will be enabled to talk very much more learnedly and technically than they otherwise could. The new score-board will add very greatly to the pleasure of the game.”

The first final score recorded on the wooden board was a 23-0 victory over the team from the USS Franklin training ship from Norfolk, Virginia.

For the next quarter century, the homemade, manually operated bulletin board in the southeast corner was NC State of the art, if not exactly cutting-edge technology. It received its game information via hand signals from Riddick’s open-air press box. In the mid-1920s, a basic game clock was installed at the opposite end of the stadium, sponsored by Pine State Ice Cream.

In 1926, to big fanfare, inning-by-inning scores of a World Series game between the St. Louis Cardinals and the New York Yankees were posted on the scoreboard during the NC State-Furman football game. The Cardinals won; the Wolfpack didn’t.

The school’s first electronic scoreboard was part of a major campus expansion during the 1930s. Beginning in 1933, the Depression-era Progress Works Administration spent six years expanding Riddick Stadium, with grandstands on the east side that bumped capacity to nearly 20,000 fans. As part of that facility enhancement in 1935, the News and Observer donated an electronic timing clock and scoreboard.The Durham Life Insurance Co., owner of flagship radio station WPTF, donated a new public address system. Duke also unveiled a bright new scoreboard with a time-clock during the same season.

However, when the scoreboard was unveiled on Oct. 19, 1935, opponent Georgia was worried it wouldn’t work properly and refused to allow it to keep the game time, relying only on the field judge’s stopwatch. The Bulldogs won 13-0.

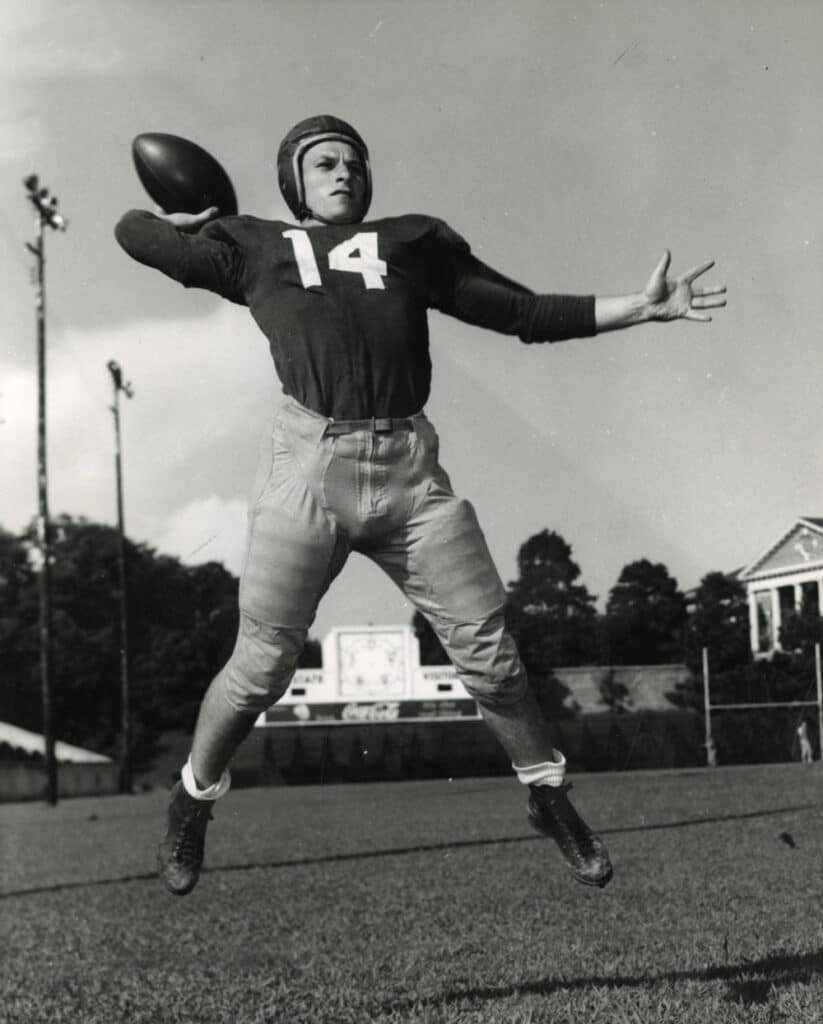

That scoreboard, sponsored by Coca-Cola, remained relatively unchanged for the next 20 years of Riddick’s service as a football stadium, although from the late 1940s until midway through the 1951 season, the scoreboard didn’t work because no one could locate a hard-to-find part that kept the minute hand on the clock turning.

The scoreboard was last used on Nov. 13, 1965, when the Wolfpack beat Florida State 3-0, the lowest-scoring home victory in school history.

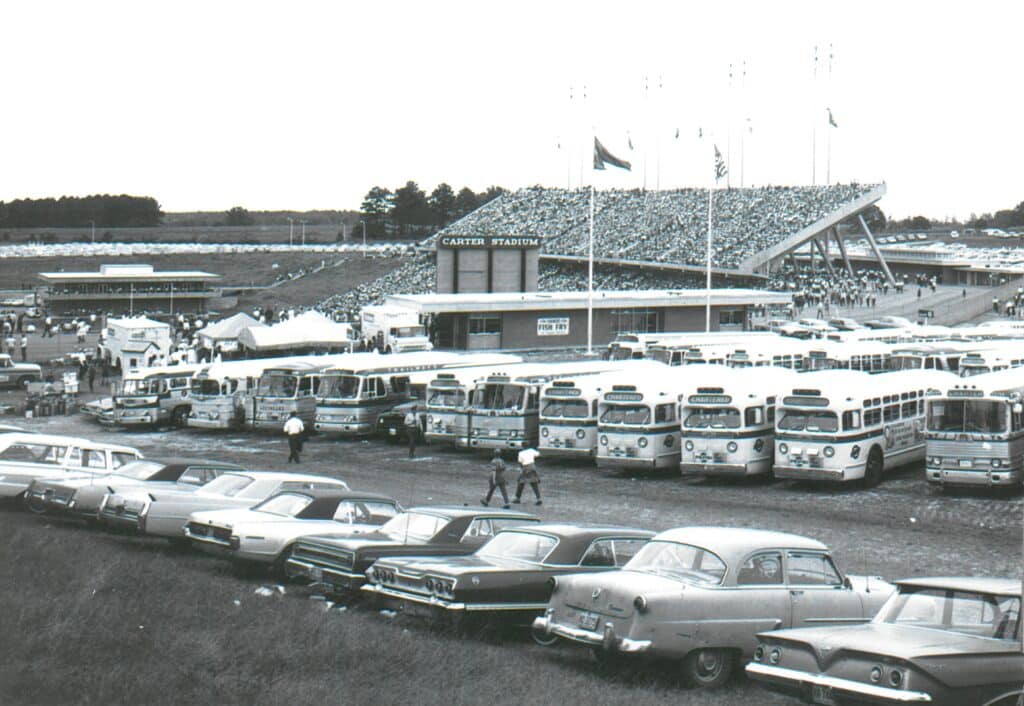

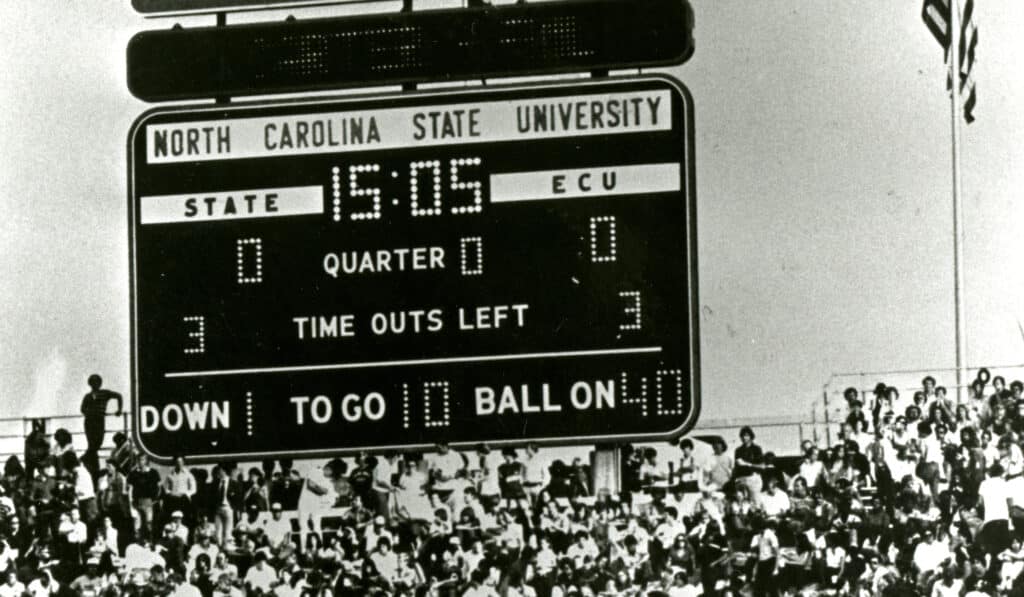

When Carter Stadium opened on Oct. 8, 1966, a giant two-story scoreboard towered over the ticket office atop the grassy bank in the south end zone. It had an up-to-date matrix display that included a clock, score, downs, timeouts remaining and possession. It displayed the totals for the two-highest scoring teams in school history in 1972 and ’73, when the Wolfpack averaged 32.7 and 33.2 points, respectively. (Those numbers stood until quarterback Philip Rivers’ junior and senior seasons in 2002-03.)

In 1985, NC State gained some notoriety when it installed one of college football’s first animated videoboards at a cost of $500,000, paid for by three title sponsors: First Union Bank, Bobby Murray Chevrolet and Coca-Cola.

Cartoon-style animations moved across the dot-matrix board, controlled by a then-powerful personal computer located in the old Carter-Finley press box. It could lead cheers, advertise local businesses and inform crowds of all necessary game information.

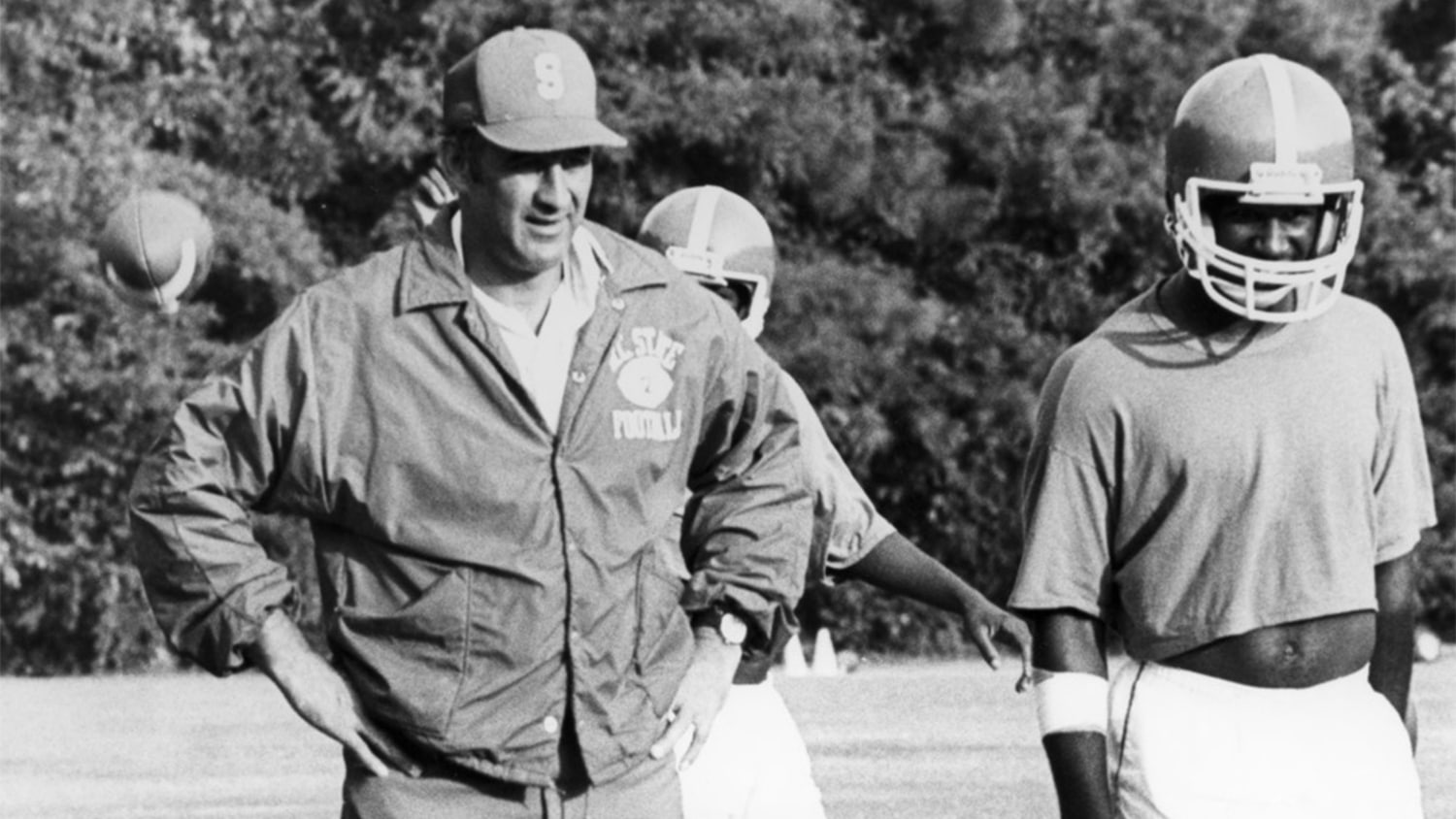

“We’re going to teach it to do this to the officials if we don’t like a call,” said then-football coach Tom Reed, waving a clinched fist in the air. “[Senior Associate Director of Athletics] Frank Weedon is going to be in charge of that.”

It was unveiled on Sept. 6, 1985, two days after President Ronald Reagan spoke to a frothing crowd of NC State students at Reynolds Coliseum about tax cuts and the need for fiscal responsibility. Technician, NC State’s student newspaper, opposed it.

“At a price of $500,000, it should sing the national anthem and run down onto the field and dance every time State scores,” said an unsigned editorial. (For the record, the Wolfpack scored 186 points that season, the fourth lowest total during the Carter/Carter-Finley Stadium era.)

It was the scoreboard of record for several of the biggest wins in school history, including the 1986 victories over Clemson and South Carolina, the 48-3 rout of North Carolina in 1988, a 28-21 win over defending national champion Georgia Tech in 1991 and the biggest upset in school history, a 24-7 win over No. 2 Florida State in 1998.

In 1995, a classified ad in Technician begged interested applicants to help run the Carter-Finley Stadium scoreboard for $6 per hour, with the caveat that any successful candidate “must be willing to work weekends.” Duties included programming the scoreboard and learning to replace receiver cards and light bulbs.

Shortly after the turn of the century, NC State athletics began a five-year, $150 million expansion and upgrade to enclose both ends of the stadium, add the Murphy Center fieldhouse, install a new press box and luxury seating tower, update the lighting system and, in 2004, add a 24–by–32-foot “Superscreen” videoboard and PA system.

Over the course of 20 years, that scoreboard was upgraded at least twice, until it was removed during the off-season to make way for what is now one of the largest videoboards for a college football stadium in the country.

- Categories: