Brain Power

Like a lot of graduating seniors at NC State, Ziad Ali is looking to the future — but not just to commencement or his first job after college. He knows what he wants to accomplish decades from now, by the end of his career.

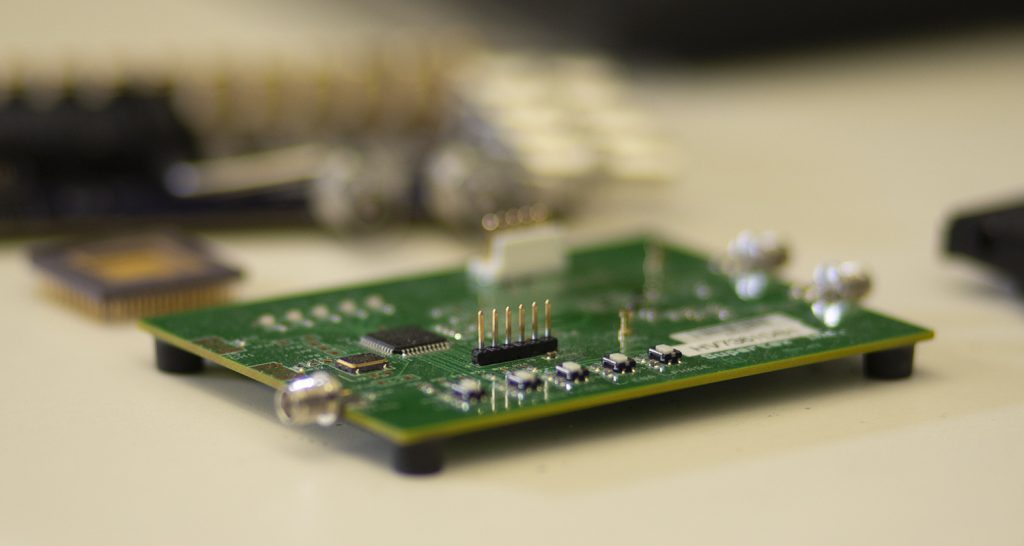

“My goal is to make a circuit that can be implanted in the brain that can completely replace the functionality of a low-level portion of the brain, like motor control,” he says. “So, for example, if you damaged a part of your brain in an accident, the circuit could replace the damaged section entirely.”

Ali, who will graduate in May with a double major in electrical engineering and biomedical engineering, can focus on his future with certainty thanks to opportunities he’s worked hard to seize since high school. The latest, a coveted Knight-Hennessy Scholarship, opens the door to a full ride at Stanford University, where he’ll pursue a Ph.D. in electrical engineering this fall.

Electrical engineering wasn’t always in the plans for Ali, who grew up in the small town of Oak Ridge, North Carolina, outside Greensboro. “Both my parents are engineers and I wanted to make my own path,” he says. “For a while, I wanted to be a chef.”

Then inspiration struck when he had the opportunity to attend a four-week summer program for high school students interested in STEM subjects — science, technology, engineering

“Being able to work on an independent project and discover things myself and then to have something work at the end, that was kind of an ‘Aha!’ moment,” he says.

He took the project to the next level in his senior year of high school, when he redesigned the device using analog circuits. “There was no microcontroller, no programming, just hardcore circuits,” he explains. “When it worked, I thought, OK, I can actually do this.”

The brain is the biggest analog circuit ever.

A Park Scholarship gave Ali the chance to attend NC State with a cohort of students united by a passion for service and learning. “The students in my class have been my best friends and collaborators for the past four years,” he says. “I live with seven of them now. We’ve bounced tons of ideas off of each other, and they’ve helped me grow. They’re all passionate about changing the world.”

The four-year scholarship, which covers tuition and fees, housing, food, books, travel costs

Engineering Meets Medicine

While the Park Scholarship sweetened the deal, Ali was primarily drawn to NC State for the quality of its engineering programs, especially its groundbreaking research in power electronics and wearable health-monitoring devices. In the

“Basically, the brain is the biggest analog circuit ever,” Ali says. “So the brain presents a lot of opportunities to match the physical circuit side with the biological side, and see where they intertwine.”

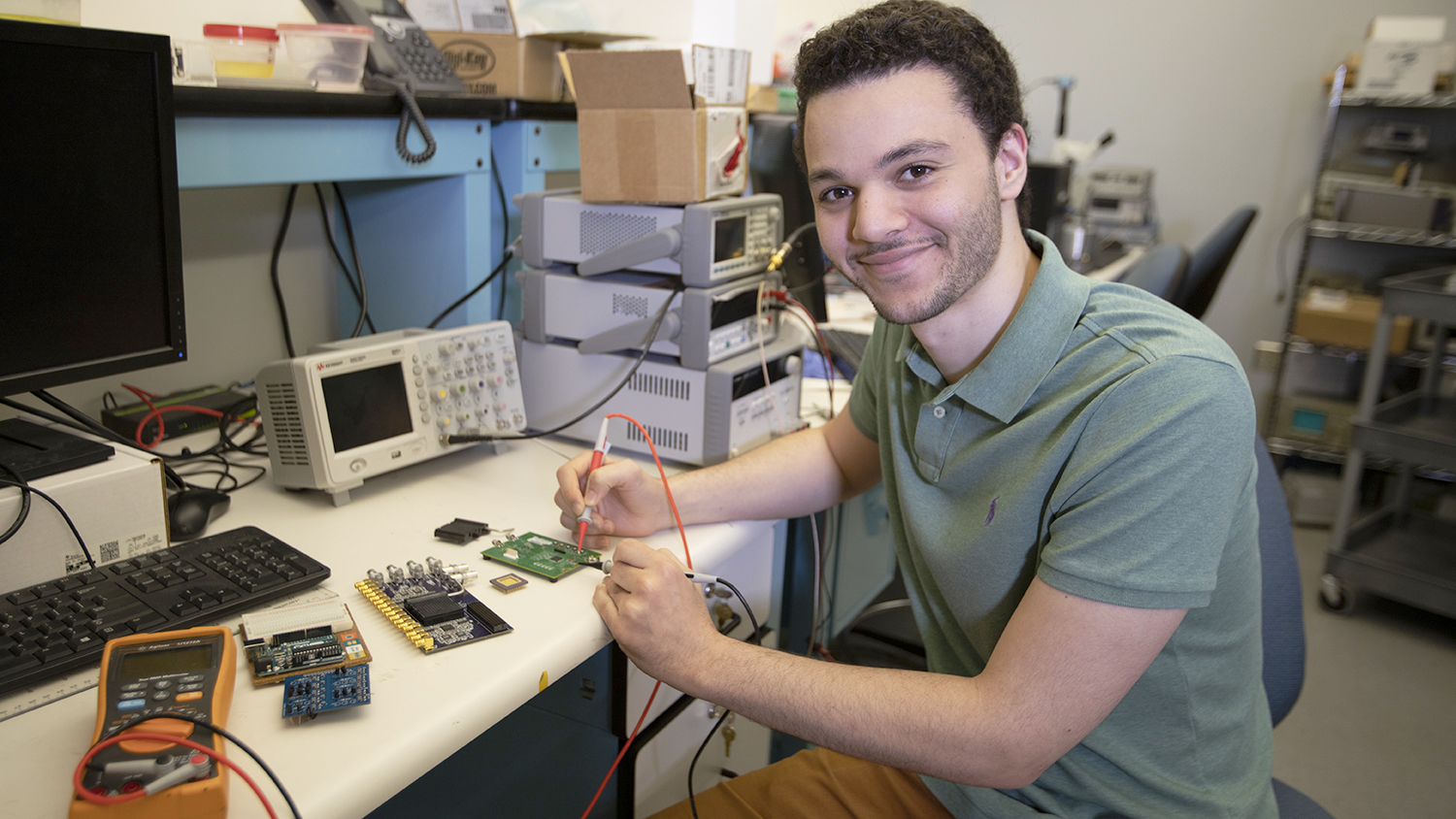

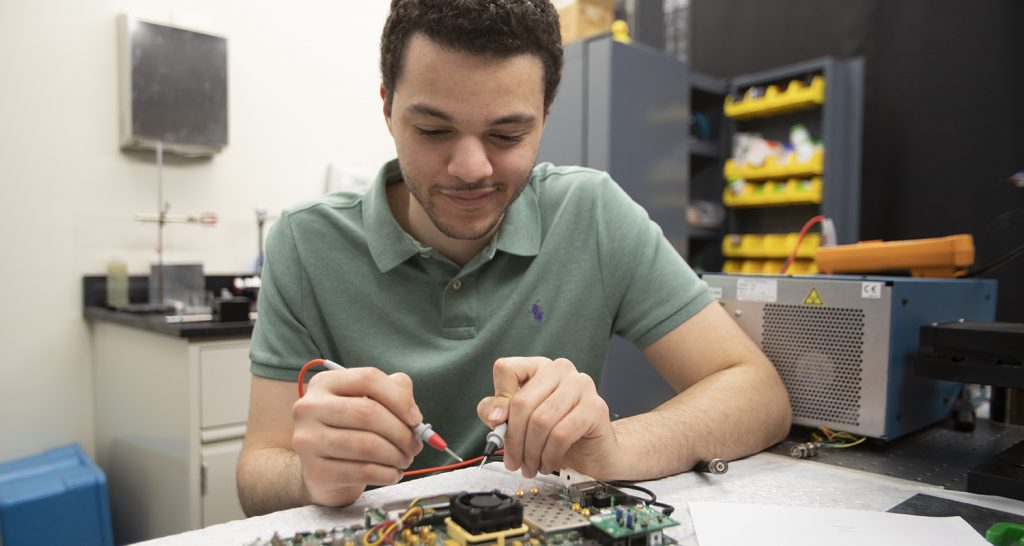

Since joining the iMIST research team during his sophomore year, Ali has thrived, developing his skills as an engineer and a researcher. He credits the lab’s director, professor Omer Oralkan, for nurturing his progress.

“I owe Dr. Oralkan a lot,” he says. “He meets with me every week, and he’s given me projects over the years to help me develop my skills as an electrical engineer. He always includes me in the group meetings so that I know what’s going on with the research at a much higher level than my particular task.”

Ali has also worked with physics professor Hans Hallen and engineering professor Alexandra Duel-Hallen to learn more about signal processing. “We’ve been working on a software simulation using low-frequency signals to predict sudden changes in high-frequency, 5G signals,” he says. “It’s been incredibly useful because when you’re developing circuits for neural applications — like brain stimulation — there are so many neural signals that have to be processed.”

On top of his classwork and research projects on campus, Ali has worked summer internship at some of the nation’s top research labs, including Sandia National Laboratories, the Olson Lab at Columbia University and the MIT Lincoln Laboratory.

Inspiring Minds

He’s also pursued a personal passion, working with the nonprofit Neighbor to Neighbor program and a team of fellow NC State undergraduates to give youngsters in the Triangle’s low-income communities hands-on training in computer science and other STEM disciplines. Ali says it’s been one of the most challenging — and rewarding — experiences he’s had since coming to NC State.

“Getting to know the kids has been awesome,” he says. “But we’ve had to completely rewrite the curriculum. We thought we’d have the kids making their own programs by the end of the first semester. Now we’re just trying to get them comfortable with the idea that they can do these things by themselves, and to get them thinking about the kinds of problems they’d like to solve.”

Ali can relate to the kids’ dilemma. When he first came to NC State, he had a much more limited focus than he does today.

“When I was a freshman, I wasn’t sure I was going to go to graduate school,” he says. “I thought I was going to make the next big app and then sell it for a billion dollars or something. Then I came to the realization that it’s hard to break into that field with something that is both highly impactful and technically complex enough

While he continued to work in app development and even founded a hackathon at NC State called PackHacks, Ali began to rethink his path.

“I figured a better use of my time would be to focus on developing fundamental technologies without necessarily focusing on making money,” he explains. “There are a lot of successful apps that don’t solve important problems. I want to solve problems that change people’s lives.”

Prepared by his research and studies at NC State and equipped with a Ph.D. from Stanford in a few years, Ali will have the rest of his life to make that vision his legacy.