Margaret Atwood and the Biotechnology of Tomorrow

The NC State community explores the line between fiction and future with a visit from the world-famous author.

On November 15, 2019, NC State hosted world-famous author Margaret Atwood for a daylong visit that included a group discussion with students and faculty, and a keynote speech: “An Evening with Margaret Atwood: Literature to Explore Our Genetic Engineering Futures,” a College of Humanities and Social Sciences (CHASS) Lightning Rod event. Her visit was sponsored by the Genetic Engineering and Society Center (GES), in collaboration with the Friends of the Library at NC State and a groundbreaking new art exhibit at the Gregg Museum of Art and Design, Art’s Work in the Age of Biotechnology: Shaping Our Genetic Futures.

As a writer, Atwood is something of a rock star. Her 1985 publication The Handmaid’s Tale was adapted into an Emmy award-winning television series. That novel’s sequel, The Testaments, was released this year and co-awarded the Booker Prize, Atwood’s second. In her decades-long career, Atwood has received numerous awards, including one, recently, from the Queen of England.

While Atwood may be best known for The Handmaid’s Tale, it’s not her only eerily prescient work. The novel Oryx and Crake, published in 2003, imagines a world where for-profit biotechnology has created designer species and changed the very nature of humanity. The first in what’s known as the MaddAddam trilogy, Atwood calls the novel “speculative fiction” rather than pure science fiction, in a nod to our current technologies and capabilities.

“Here we have not just fiction, but fiction rooted in scientific possibility,” says Molly Renda, exhibits program librarian for NC State. “What we’re presented with might be possible in our lifetimes. It’s not just fantasy.”

Through her symposium with students and faculty and her evening address, Atwood’s visit to NC State spotlighted the biological and societal outcomes she explores in Oryx and Crake, and our collective responsibility for thoughtful innovation as technology outpaces regulation — and sometimes public comprehension.

Synergy on Campus

Bringing together literature, science and art to comment on the future of genetic engineering is no small feat. “It feels like the culmination of everything the center has been working towards for the past five years,” says Patti Mulligan, communications director for the GES Center.

Fred Gould, the center’s co-chair and the William Neal Reynolds Distinguished Professor in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, collaborated with Renda on the idea of a biotechnology art exhibition before approaching the Gregg Museum and pitching to guest curator Hannah Star Rogers. The idea to bring Atwood to campus was championed by Jennifer Kuzma, Goodnight-NCGSK Foundation Distinguished Professor in the School of Public and International Affairs of the College of Humanities and Social Sciences, and co-chair of the center with Gould.

“We built the GES Center to take on the challenge of elevating the conversation about engineered crops, insects and animals with a goal of becoming trusted voices. The Gregg exhibit and the Atwood visit are all part of our effort to bring diverse voices into the conversation to help our students and the public think more deeply about the current and future implications of genetic technologies,” says Gould.

Through various colloquia and faculty talks, the GES Center strives to look at all angles of genetic engineering issues. Consulting fiction, however, is a new approach.

“I love Margaret Atwood’s goal of using literature to show people a dystopia that is really possible in order to get us to think more carefully about how we guide the use of genetic technologies,” adds Gould.

In Her Own Words

Recently named one of “100 Novels That Shaped Our World” by the BBC, Oryx and Crake covers a host of issues including genetic manipulation, corporate domination and global pandemics.

Atwood’s afternoon symposium featured students from the MFA in Creative Writing program; a class on science, technology and society; women and gender studies; and this semester’s GES Colloquium. Students’s questions ranged from concerns about who should have access to what knowledge, and the responsibility that comes with that, and the role of fiction in exploring the world of human genetic experimentation.

When asked if the path we’ve started down will continue unchecked, Atwood offered a scientific reply. “As you know,” she said, “nothing is inevitable. There are too many variables.”

Students reacted to the visit with keen excitement. “Getting the actual artist’s point of view on their work, in person, is rare,” said Hannah O’Kelly, a sophomore studying sociology. “You can only go so far trying to figure out what an author really means, and having the chance to ask her yourself is pretty astonishing.”

Roshan Panjwani, a junior studying linguistics, said, “This book, and reading it in this political moment, has felt really important. It’s helped us have a more critical lens on the applications of technology. As students, we can be part of a new generation of critical scholars and decide how we want to shape the world that we’re inheriting. So having an author like Margaret Atwood come to NC State is just incredible.”

Atwood discussed the uses of fiction to help illuminate some of the murkier possibilities in the intersection of biotechnology and society. Human imagination is a strong driver for scientific discovery. “We seem to be inclined toward a certain amount of magical thinking,” said Atwood.

“Her work has made us reflect on where we’re headed as a society,” said Jendayi Brooks-Flemister, a master’s of fine arts student with a fiction concentration. “Why are we here now, and where are we going? In this climate, that’s such an important question to ask.”

After the student symposium, Atwood entered the State Ballroom in Talley Student Union to a standing ovation, before sharing her thoughts on how she uses literature to explore our genetic engineering futures.

“Human desire is driving these choices,” she said. “Is that an ethical compass?”

A Voice in the Future of Biotech

Divining the future is not just the realm of artists and writers; it’s happening in the lab. The pace of discovery in genetic engineering has wide-reaching implications, beyond the test tube or even the grocery shelf. Experts at the GES Center are working hard to integrate public values and scientific knowledge as the futures of biotechnology take shape.

Aside from co-chairs Gould and Kuzma, the GES Center is supported by an Executive Committee of three faculty and two staff, plus a cohort of more than 50 affiliated faculty.

It’s part of the Chancellor’s Faculty Excellence Program, which clusters faculty and researchers from across disciplines to help solve major challenges facing society at large. In its unique integration of the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences, the GES Center tries to anticipate new biotechnologies and their potential consequences and associated concerns. It seeks to answer the question of not just can a thing be done, but should it?

Though just five years old, the GES Center had a sizable impact on the world of genetic engineering research and policy. “There’s no other place we’re aware of in the world that approaches questions about genetic engineering and biotech in the way that we do,” says Mulligan.

The idea for hiring a cluster of faculty working on questions related to genetic engineering and society came primarily from Gould, an internationally acclaimed expert in the field of genetic engineering. As an entomologist, Gould brought NC State into some of the earliest conversations — and controversies — about genetically engineered insects and crops. Kuzma, the lead hire in the cluster, proposed a plan for building the cluster into a major university center that could interface with the public, policy makers, and researchers.

Aside from much-hyped theoretical concerns about designer babies and frankenfoods, the real issues are complex and hard to tackle. Science is approaching the third generation of genetic engineering, where instead of inserting foreign DNA to match desired properties, we’re now able to edit genetic material directly using technologies such as CRISPR, an elegant cut-and-paste method that borrows a trick from a natural immune process found in bacteria. Scientists could, for example, turn off the gene that makes a bull grow horns. Still, should they?

Gould sees the center’s charge as keeping the conversation transparent surrounding genetic engineering and biotechnologies. The GES Center receives no funding from biotechnology corporations, nor is it supported by anti-genetic-engineering NGOs. They’re able to approach the topic from a strictly research and academic standpoint, with some of the brightest minds in the industry.

“There’s tremendous overlap between scientists, consumers, policy makers and other people who will try to tell the story of what advances in biotechnology mean for society. That sets up the possibility for a lot of uninformed decisions and influence on all sides,” says Mulligan. “We sit in that nuanced area where no one likes what we’re saying.”

These technologies don’t stay in the lab forever. Scientific discovery evokes public sentiment and eventually government regulation, and that’s were Kuzma comes in.

Widely published and frequently interviewed on the topic of genetic engineering regulation, Kuzma helps lawmakers understand the science behind broad policy regulations and their impact on others. She’s an expert on risk analysis and international governance, which comes into play with some of the more theoretical ideas the GES Center faces in the future of biotech. If a gene-edited mosquito is released in one country, for example, there’s nothing to stop it from flying to another.

When future-casting societal concerns surrounding transgenic creatures and crops, fiction like Atwood’s can stir up fears. Kuzma sees that as a good thing.

“I don’t think that dystopian speculative fiction about biotechnology is harmful at all. In fact, I think it is essential. Speculative fiction like Oryx and Crake is crucial to help us understand what we do and do not want for a future with biotechnology. Atwood writes about the possible and plausible so that it does not become probable,” she says. “So we wake up, create opportunities for public voice and choice, and help to guide genetic engineering in responsible ways.”

Conversations surrounding biotechnology and society can get heated, and the GES Center has adopted a statement on “productive, inclusive and ethical communication.” The point is not to avoid disagreements, but to use them to learn. There’s even a line that specifically encourages emotional, creative and performative expression.

It’s as though they were planning on an art exhibit all along.

From the Lab to the Art Gallery

In 2019, it’s not unusual for lines to blur between biology and art, progress and ethics, information and inspiration. Art’s Work in the Age of Biotechnology: Shaping Our Genetic Futures is proof of how relevant these topics are becoming. The exhibit challenges our understanding of the human condition, the material of our bodies, and the consequences of biotechnology.

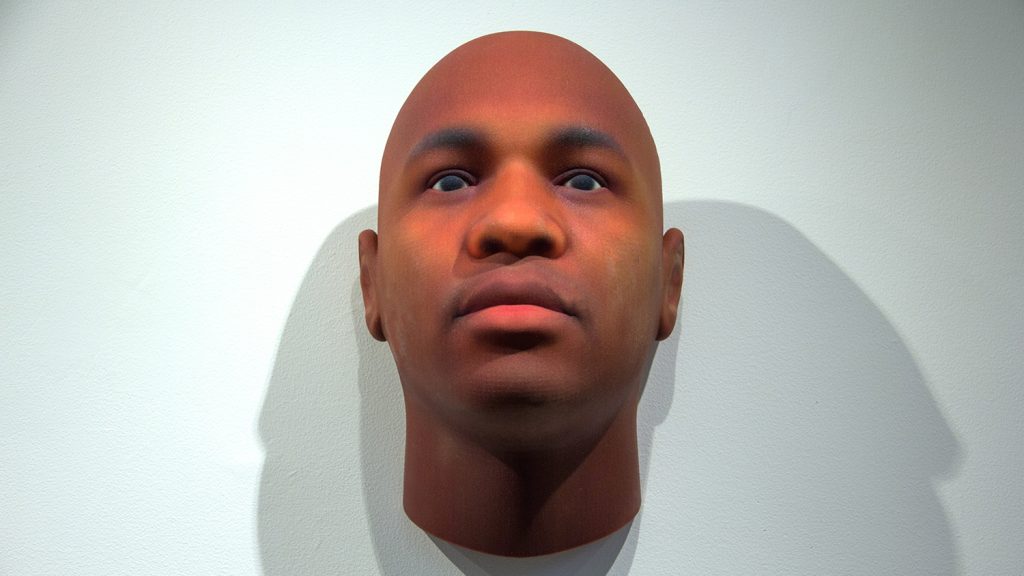

Upon entering the gallery, visitors are greeted by a series of 3D-printed faces mounted over the bio-tinged detritus — cigarette butts, chewing gum — that inspired their futuristic police sketches.

If detectives can use DNA to nab killers, should they also use it to nab people who litter? What does spit have to do with facial recognition software? Should we try to cool the planet? What do our lives become when they are no longer ruled by chance or biology, or even free will?

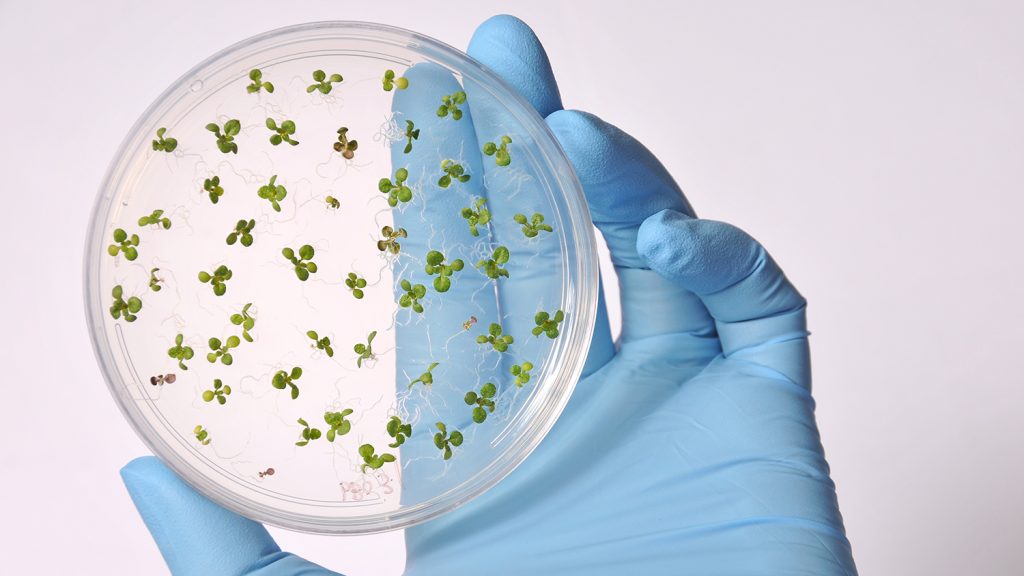

One work in the exhibit, We Grow Our Own Luck Here by Ciara Redmond, selectively grows four-leaf clovers by the flowerpot-full. By taking something rare and selectively commodifying it, have we made more luck for ourselves, or have we ruined it?

“Sometimes what’s actually happening is more thought-provoking than what fiction can come up with. Sometimes the reverse is true,” says Evelyn McCauley, marketing and communications coordinator for the museum. “I think this exhibit addresses the comparison of what science fiction has commented on regarding genetics and humanity, and what’s actually happening.”

The exhibit is fundamentally different from others hosted by the Gregg. Special materials like live mice and live plants meant special considerations. And it’s spread across four venues: Hunt Library, D.H. Hill Jr. Library, the Gregg, and, temporarily, outdoors at the North Carolina Museum of Art. The artists themselves are from disparate fields and different countries, including Ireland, Britain and the Netherlands. Finally, the subject matter is unusual: a STEM focus interpreted by artists, in novel ways.

“The exhibit takes the tools of art and blends it with the tools of bench science,” says Renda. “It creates an experience that gives access to a subject that’s all around us but might not feel approachable.”

A question the exhibit hopes attendees ask themselves is: Just because you have an idea and a way to make it happen, should you do it? One of the most popular pieces at the opening was Errorarias: Bipolar Flower Enrichment, by Adam Zaretsky, an interactive installation that features a terrarium filled with plant life and a changeable environment, with lights and sounds controlled by knobs and dials. Visitors are encouraged to think about how their whims can affect living things.

“Sometimes it’s uncomfortable,” says McCauley. “Sometimes we imagine that biotech is this Pandora’s box that we don’t want to open, when in fact, it’s benefited society in ways we’re not even aware.” For example, Kerasynth, an experiment in synthetically manufactured fur and wool, poses a solution that’s as beautiful as it is animal-friendly.

One artist was specifically inspired by Atwood’s Oryx and Crake. In Laboratory Life, Suzanne Anker’s layered photographic images evoke the quotidian experience of working in a lab, suffused with a biological explosion of plant life run amok. Anker gave Atwood a personal tour of the exhibition during her visit.

Ideas for future collaborations formed as the artists came together, a nod to the synthesis happening all over campus during this event.

- Categories: