When a Norovirus Expert Got Norovirus

Editor’s note: This is a guest post by Liz Bradshaw, a postdoctoral research scholar in NoroCORE – the Norovirus Collaborative for Outreach, Research, and Education, based at NC State. The post is part of a series on food safety leading up to World Health Day on April 7.

Knowing about one in 15 Americans gets norovirus every year, I’ve had the “When the NoroCORE blogger got norovirus” post waiting in the wings for a while. I think the virus has a good sense of ironic timing.

Through pure coincidence, one weekend last month was the Gastropocalypse in our home. My husband was first, with a sudden onset of some truly spectacular vomiting and diarrhea in the dead of night. Being the dutiful, loving spouse that I am, I left bleach, nitrile gloves, medications, and paper towels outside the bathroom door and set up basecamp in the guest room.

Knowing my time might be nigh, since norovirus gets around (fun fact, it can be aerosolized over several feet when a person vomits) and has a 12-48 hour incubation period, I dashed to the grocery store at first light for enough bland foods, cleaning supplies, and tummy meds to last us a week. (In a perfect world, I would have had everything on-hand ahead of time, and not risk spreading my cooties around, since you can shed the virus before showing symptoms, but we were laughably low on toilet paper.) Sure enough, by that night I was feeling pretty puny, with demonic tummy rumblings and waves of chills, aches, and nausea.

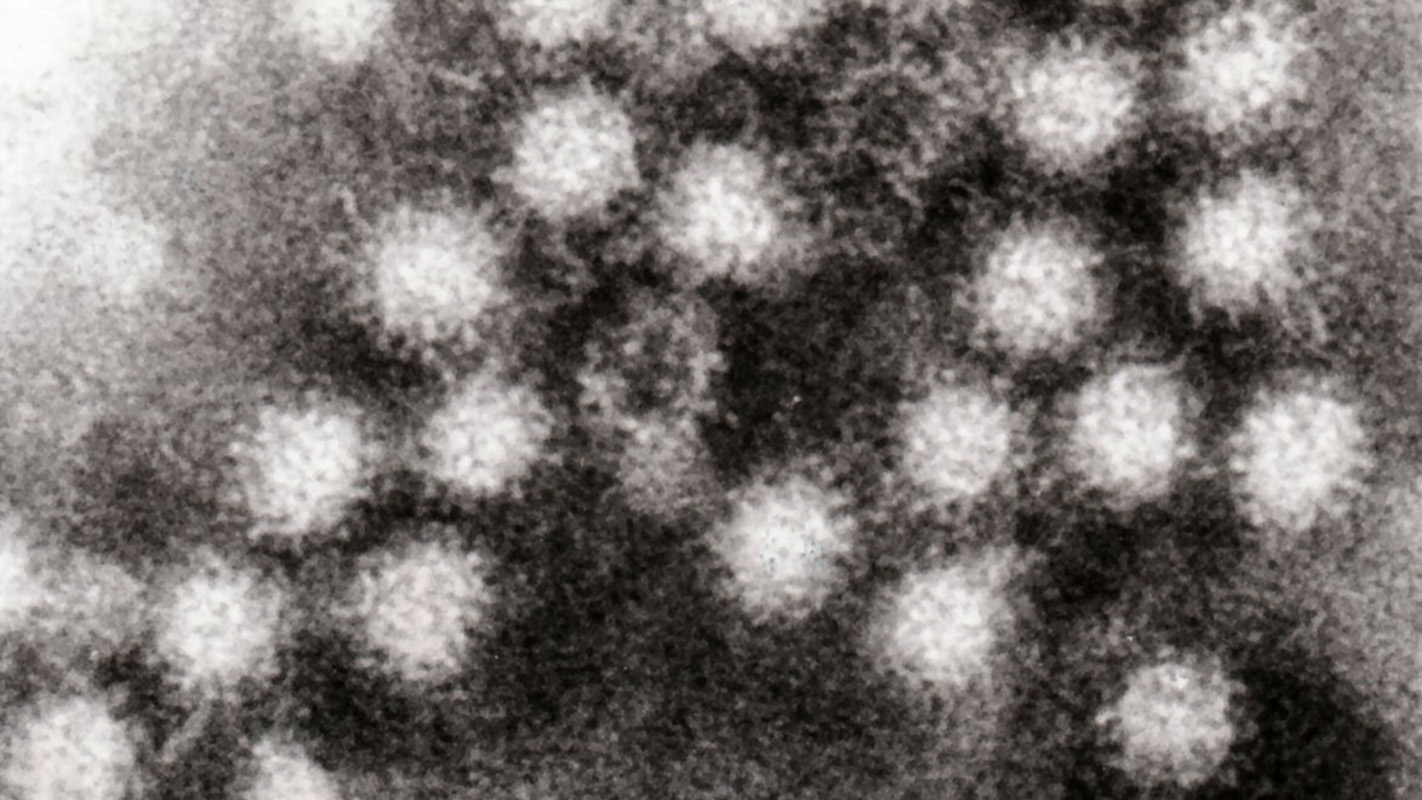

Truth be told, we don’t know that it was actually norovirus, and if it was, we can only guess as to how we got it. Noroviruses are typically spread through direct person-to-person contact, through consuming contaminated food or water, or through encountering the virus in the environment. Hypothetically, someone with the virus on their hands could have touched the same doorknob or menu my husband used when he visited a restaurant over the weekend, or it could have been in the food he ate, and I likely got it from being in contact with him or our contaminated apartment.

The key part to understanding the food safety aspect is that food can be contaminated at any point from farm to fork, and we usually associate foodborne norovirus outbreaks with foods that are served raw or minimally cooked, or like the sandwich my husband ate, ones that are prepared by hand. About one quarter of all norovirus outbreaks in the United States are associated with the consumption of contaminated foods.

It is thought that 90 percent of people with norovirus do not seek medical attention and manage their symptoms at home, like we did, so those cases don’t get diagnosed, reported, and tallied by groups like state health departments or the CDC. But that doesn’t mean the illness isn’t a big deal, and we think that noroviruses are the leading cause of acute non-bacterial gastroenteritis – and the most common cause of foodborne illness in the U.S.

Looking at the big picture, it’s estimated that 20 million Americans get norovirus each year, at a cost of $2 billion. Though the vast majority of people get better after a couple of memorable days, it is believed as many as 800 people in the U.S., usually the young, elderly, or immunocompromised, die from the disease. When infected, people shed the virus in the millions to billions in their stool and vomit, and the virus can persist on surfaces, foods, and in water for weeks or more. There are several things people can do to prevent getting and spreading norovirus, which the CDC does a great job of explaining.

North Carolina State University plays a unique role in this story and promoting public health by being the home institution for NoroCORE. NoroCORE stands for the Norovirus Collaborative for Outreach, Research, and Education, and it is funded through a $25 million grant awarded by the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture. The collaborative includes over thirty research teams from eighteen institutions around the country, and teamwork and bringing different disciplines together to make actual impacts are the name of the game.

NoroCORE works towards its goal of reducing the burden of viral foodborne illness by approaching the problem from multiple angles, in the form of six cores: Molecular Virology, Detection, Epidemiology & Risk Analysis, Prevention & Control, Extension & Outreach, and Capacity Building.

Research is a big part of NoroCORE, to better understand the virus, how it affects us, and how we can manage it, but there is more to the picture. NoroCORE also gets feedback from around 100 stakeholder organizations to ensure that the research and tools that are developed are practical and relevant. NoroCORE also reaches out to other researchers in the field in the form of funding awards, and fosters the next generation of food virologists by awarding annual graduate fellowships.

For example, NoroCORE researchers here at NC State are investigating how far the virus particles can travel when a person vomits, its persistence in the environment, how analogs of the particles (termed virus-like particles) interact with detergents and surfaces, and how social media can be used to educate audiences about food safety. Some of our collaborative institutions are working on culturing the virus, understanding its spread within human populations, and developing better detection methods.

In short, NoroCORE blends the expertise of researchers, educators, and extension specialists from institutions around the country with the perspectives of those in industry and government organizations. Their goal is to bring about positive change and make advances in the fight against foodborne viruses, accomplishing more together than the relevant participating groups could do alone.

Note: This year’s World Health Day focuses on food safety. Previous posts in this series address the health and economic importance of food safety, listeriosis, and campylobacteriosis.

- Categories: